My Home Screen in Feburary ’24

Posted on from Frankfurt, GermanyEvery month, I’m sharing my current home screen.

Every month, I’m sharing my current home screen.

I’m addicted to my phone. You are probably too.

And I’m trying to fix this: I don’t have TikTok or Instagram, I only use YouTube in Safari with Shorts blocked, and I use one-sec for apps that I don’t want to waste my time on. But still, time-sinks keep creeping in after a week or two.

So, I did what I wanted to do for years: I put my iPhone at my desk and left it there for 7 days. Here’s how it went.

Every month, I’m sharing my current home screen.

This year I’ve read over 500 articles for my newsletter, Arne’s Weekly. For this post, I’ve distilled them down to the ones I liked the most and/or that had the biggest impact on my life.

Here they are, in no particular order:

What were your favorites? Let me know!

This is the second post in my Emacs From Scratch series.

In Part 1, we’ve set up the UI and evil mode. Today we’ll set up a way to manage projects, quickly find files, set up custom keybindings, interact with Git and open a terminal inside Emacs.

Vim is usually terminal-first; you navigate to a directory and open Vim. Emacs is the other way around; you start Emacs, open a project and maybe a terminal buffer (see Terminal further down).

Let’s set up Projectile to manage our projects and quickly find files.

You can now run M-x (a.k.a. Opt-x on macOS) and type

projectile-add-known-project to add a project as well as

projectile-switch-project to open a project.

This is neither fast, nor discoverable. Let’s set up some custom keybindings.

Before we define our own keybindings, we need to do something to improve discoverability. which-key will show available commands as you start a keybinding sequence:

We’ll use general.el because it makes

it super easy to define keybindings and allows us to define them in a

use-package function.

We’ll have SPC as our leader key, which allows us to press SPC and have all our custom keybindings show up.

We’re using :which-key to add a description that will show up next to the

command.

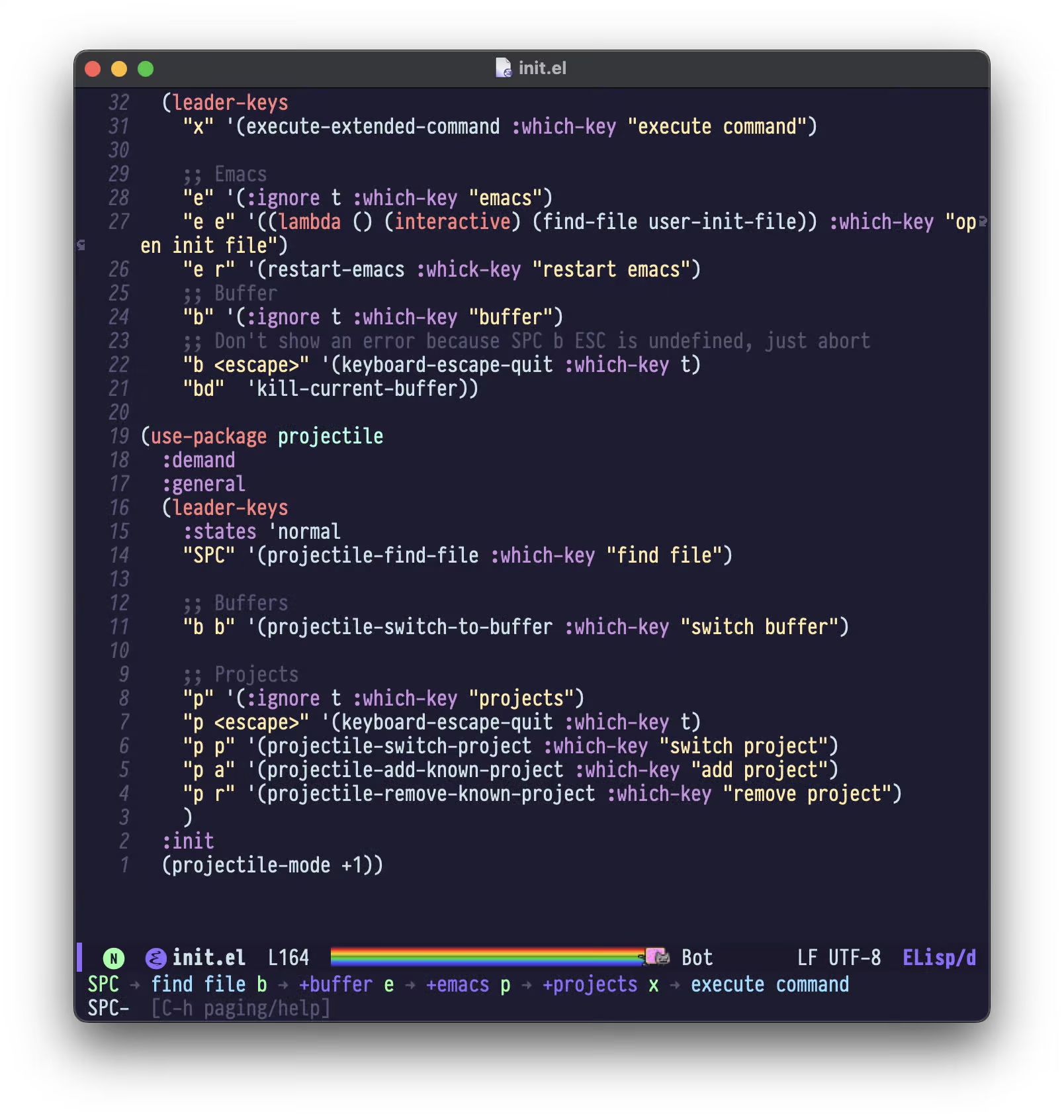

To add custom keybindings to Projectile, we need to edit the use-package

definition and move it after the use-package general function:

Now we can press SPC and get suggestions that we can navigate along.

SPC SPC lets you open a file in the current project (or a project if none is open),

SPC b opens buffer options, SPC p project options, etc.

This is what it looks like:

But when you try to find a file, or add a project, you’ll notice that this is clunky as you need to type the exact path for it to work. Let’s fix that.

We’ll be using ivy as our generic completion frontend. This will make choosing files and projects a lot more ergonomic:

Now we get a list of possible entries and live-search.

To manage source control, we’ll use Magit, which is–rightfully–widely considered to be the best Git client ever:

To make Magit work nicely with Evil, let’s add evil-collection:

In addition we need to add this to the :init block of use-package evil to

prevent evil and evil-collection interfering:

Now SPC g g will open up the current Git status.

You can stage single files with s, all files with S and commit by pressing cc.

Finally, we want to highlight uncommited changes in the gutter:

Even though we’ll try to make everything work from inside Emacs, sometimes it’s just quicker and easier to have a shell.

We’ll use vterm as a terminal emulator we can use inside emacs.

We’ll also install vterm-toggle, a package that allows us to toggle between the active buffer and a vterm buffer:

Pressing SPC ' will open a terminal. Pressing it again will hide it, but keep any processes running.

As every time, we’ll do a few small tweaks:

Ctrl-u work like in VimAdd the following to the :init block of use-package evil:

We want similar behaviour to commentary.vim and comment objects in/out with gc:

We’ll use GCMH, “the Garbage Collector Magic Hack”, to minimize GC interference with user activity:

Move this up to be the first package loaded after configuring use-package, to improve start-up time.

If you want to exit a menu, <escape> is the key of choice, esp. coming from Vim. Let’s match that behaviour:

We now have everything we need to manage projects, navigate to files, run terminal commands and manage Git. Starting with this post, I’m using this very setup to edit this series.

In part 3, we’ll set up Tree-sitter and, if available, LSP for Rust, Go, TypeScript and Markdown.

Subscribe to the RSS Feed so you don’t miss the following parts, and let me know what you think!

Instead of setting a fixed goal as my New Year’s resolution, only to then not even make it through January, I’m setting Yearly Themes. CGP Grey has a great video on them, here’s a quote:

For some things, precision matters, for others, it doesn’t and when trying to build yourself into a better version of yourself, exact data points don’t matter. All that matters, is the trend line.

Yearly Themes act as a signpost to give your year a direction—the idea is to keep them in mind when making decisions, no matter how small.

My 2023 started with two themes:

In the past, most of my side projects were open-source and/or non-profit. I wanted to dive into figuring out if side projects with actual revenue was something I wanted to pursue.

I have a desk job and work from home and while I enjoy watching outdoor media, I have very little actual experience.

In the second half of 2023 I switched themes1 to:

My time is mostly divided into family, work, side projects and leisure. I want to be conscious of keeping a balance in my time invested.

I’m okay with how Year of Business and Year of Adventure went; I have a better idea of what it takes to turn a hobby project into something that generates revenue, and we’re leasing an orchard2.

Year of Balance went really well, I’m now doing a better job allocating the time to what’s important to me.

These are my Yearly Themes for next year:

I’ve made progress in many areas in my life over the last few years. I feel like that created “gaps” in some less interesting areas. This year, I want to invest in these areas to raise the overall base-line of myself.

After doing Year of Health at twice, I aim to focus on improving, instead of maintaining, my fitness. One metric for this could be my VO₂ max, which my Apple Watch conveniently automatically records for me3.

Do you do New Year’s resolutions or Yearly Themes, or something entirely different? What do they look like? I’d love to hear from you.

Yes, you’re allowed to do that. ↩

Not really adventurous, but hey, I’m outside more! ↩

Thankfully, it still has an oxygen sensor ↩

Welcome to my new series Emacs From Scratch. I’m far from an Emacs expert, so join me in my quest to figure out how to create a useful Emacs setup from nothing1.

In this part, we’ll install Emacs, set up sane defaults, packaging and do some basic UI tweaks to build a solid foundation.

On macOS, everyone recommends Emacs Plus. For other systems, check out Doom’s Emacs & dependencies documentation.

We’re running this command:

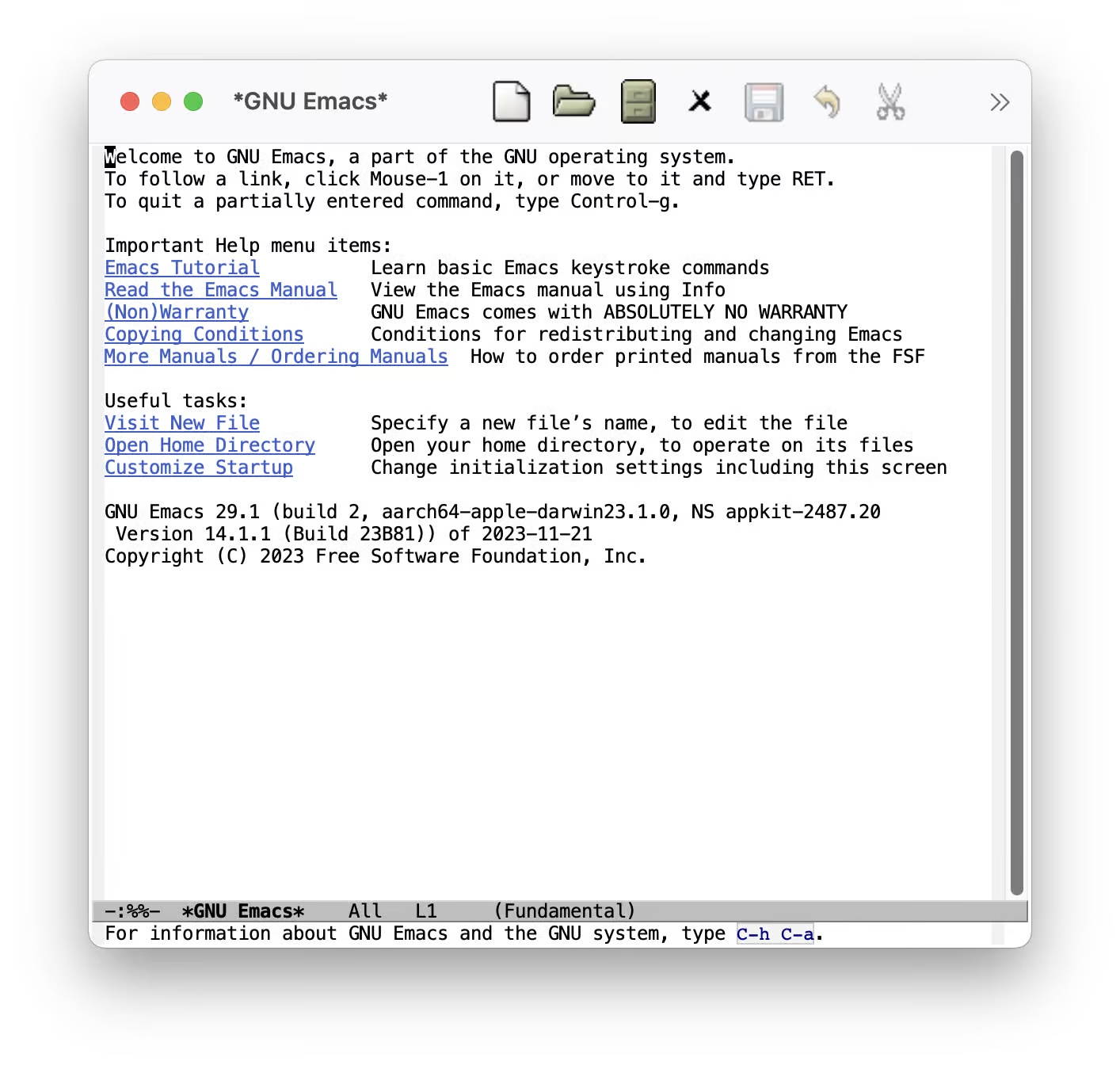

And this is what it looks like when we start Emacs for the first time:

We want to remove everything but the text. To do so, we first create a file in

$HOME/.emacs.d/init.el.

; Hide the outdated icons

; Hide the always-visible scrollbar

; Remove the "Welcome to GNU Emacs" splash screen

; Ask for textual confirmation instead of GUI

If you start Emacs now, you’ll see the GUI elements for a few milliseconds.

Let’s fix that by adding these lines to $HOME/.emacs.d/early-init.el2:

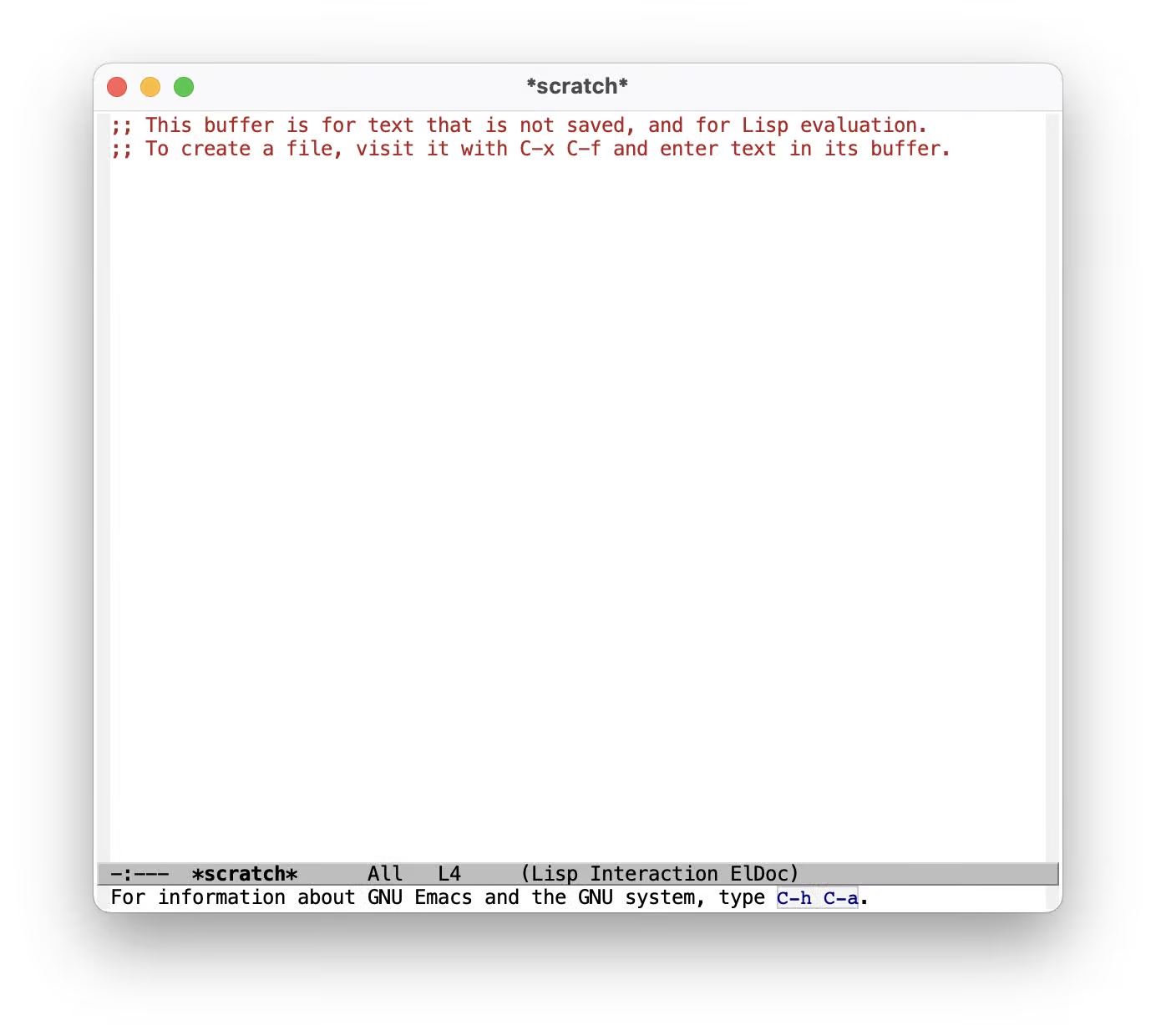

This is better:

We’ll take care of the default scratch text and the C-h C-a hint down below.

We’ll be using straight.el

for package management.

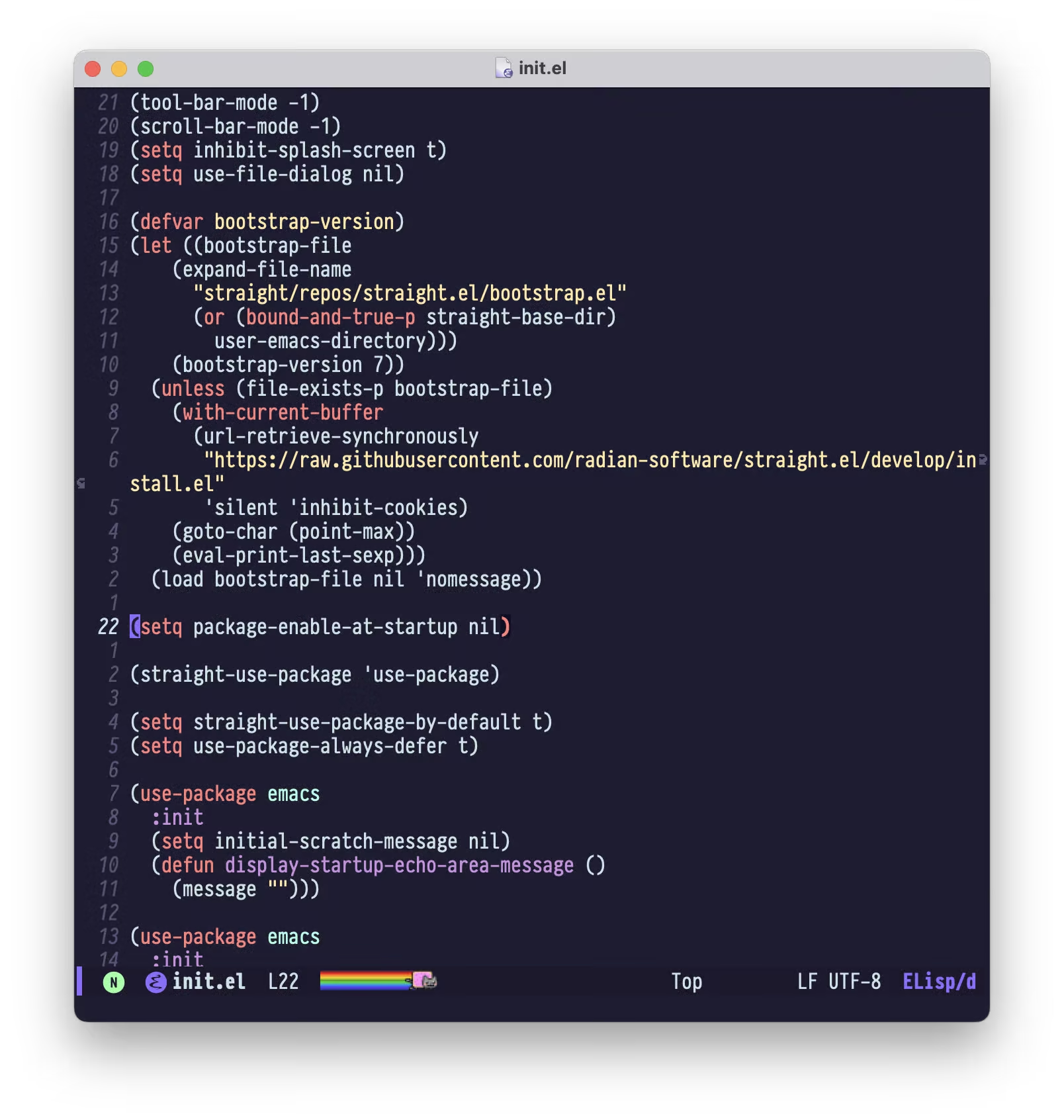

This is the installation code from the straight.el README:

The docs also recommend adding this to our early-init.el to prevent

package.el from loading:

Next we’ll install use-package for tidier specification and better performance:

Then we’ll make use-package use straight.el by default and always :defer t

for lazy loading:

It’s good practice to specify Emacs-specific settings in a use-package block,

even though this doesn’t change anything functionally.

In the following, I’ll repeat the use-package emacs function, but you can,

and probably should, move these all into a single use-package block.

Let’s start without the default scratch message and the text at the

bottom saying “For information about GNU Emacs and the GNU system, type

C-h C-a”:

In confirmation dialogs, we want to be able to type y and n instead of

having to spell the whole words:

Make everything use UTF-8:

Use spaces, but configure tab-width for modes that use tabs (looking at you, Go):

Map the correct keybindings for macOS:

I’m used to Vim keybindings and want to keep them, so we’ll use evil:

We’ll be using the PragmataPro typeface:

For themes, I can recommend the

Doom Themes, we’ll be using

doom-challenger-deep3:

Finally, we want relative line numbers in prog mode:

We’ll install doom-modeline:

For pretty icons, we need to install nerd-icons as well:

After restarting Emacs, run M-x nerd-icons-install-fonts (Option-x on

macOS) to install the icon font.

And we’ll install Nyan Mode, a minor mode which shows a Nyan Cat (which is 12 years old at the point of writing this) in your modeline to indicate position in the open buffer.

This is what looks like:

We have sane defaults, we can open a file with :e, navigate around and we

have a nice color scheme4 and modeline.

Here’s the the final init.el

and early-init.el

In part 2, we’ll add a project manager, our own keybindings, the best Git TUI, a handy shortcut to restart Emacs and a ton of small tweaks.

Subscribe to the RSS Feed so you don’t miss the following parts, and let me know if I missed anything foundational!

If you don’t want to have to configure everything and just want an editor that,

works, use VS Code check out Doom Emacs. ↩

early-init.el is loaded during startup, see The Early Init File.

Unless explicitly noted, configuration should go in init.el. ↩

Derived from the incredible original ↩

Yes, I know that’s what they’re called in Vim. ↩

Every month, I’m sharing my current home screen. This is the one for December 2023.

I’m turning 30 this year.

Inspired by Kevin Kelly’s incredible 68 Bits of Unsolicited Advice, I collected bits of advice I’ve picked up over the years—mostly by people wiser than me.

The year is 1996. You feed your Tamagotchi, get a Squeezit and turn on the home computer. You’ve told your family they can’t do phone calls for the next hour. The dial-up modem makes beeping sounds. You’re online.

Yesterday you found this fly website about amateur radio, and you want to explore more—but how can you find related websites? Yahoo is slow and not really showing you what you’re looking for. Then you notice that this website is part of the “Amateur Radio Webring”. You click the arrow to the right and dive into another website about amateur radio.

Yesterday, while looking through a folder called old things lol glhf, I fell

into a rabbit hole of old abandoned projects—mostly websites and graphic

design, but I also found one or two Flash projects and compiled .exe

files.

And, while it was really fun remembering projects I’ve long forgotten, there was no structure, and it was often difficult to figure out what a project did and what it looked like—some even missed crucial data. This made me think about how I want to archive my projects going forward.

Every month, I’m sharing my current home screen. This is the one for November 2023.

In episode 097 of the Hemispheric Views podcast, the hosts discuss their app defaults, which has inspired some people to share their own.

I’ve used a lot of static site generators in the past, and they all have their own features and quirks, but most importantly, you have to architect your website to match what the framework expects.

Since yesterday, this website has been powered by my own SSG. It’s not meant to be reusable, it’s just normal code—parsing and generating files for this specific website.

And oh boy do I love it.

Have you every shared a link to a friend and wondered where the image preview

came from?

That’s the Open Graph Protocol, a set of HTML <meta>

extensions that can enrich a link, originally invented at Facebook.

This blog post describes how you can generate these images on build time in

the Astro web framework.

You probably don’t like email, not a lot of people do. That’s because you’re using it wrong.

Chances are that if you look at your inbox, it’s full of unsolicited marketing emails, log-in notifications or spam. Or you’re doing inbox zero and all that trash lives in your archive.

As everything else, email is subject (hah) to entropy. If you’re not careful, chaos will take over.

A few weeks ago, the hard drive (yes, I know) in my home lab died. It was a sad moment, especially because I ran Plex on it and rely on that for my music and audiobook needs.

The upside is that it gave me the opportunity to rethink my Plex setup. Hosting it at home is great for storage costs and control, but it’s hard to share with friends or access on the go, especially with a NATed IPv4, so I decided to move to the cloud.

The last two weeks I’ve spent quite some time on evenings and weekends to work on an iOS app. I won’t tell you what it is though, it’s way too early for that.

This is the first post in a series and this one is about technologies and tooling.

This is the second post of my series Automate.

On the Cortex podcast (which inspired the whole series), CGP Grey and Myke Hurley sometimes talk about their checklists; whole projects that can be invoked by a tap if needed. These lists are for things that are important to get right, but you do them not often enough to remember every step, examples are an Airport or a YouTube checklist. They mostly use OmniFocus for this, which can export and import projects as TaskPaper.

This is the first post of my series Automate.

In this post I describe how I created an Automator application, which will record the latest episode of a Spotify podcast, fill out metadata like title and description and generate a file for metadata for a podcast client to subscribe to.

I listen to a lot of podcasts every day, e.g. when doing chores or commuting. One of the shows I particulary enjoy recently is Cortex, where Myke Hurley and CGP Grey talk about their ways to be productive. Every year, they define yearly themes, which are a bit like new year’s resolutions, but instead of hard targets, they are more like directions in which you want to go. I highly recommend listening to the Yearly Themes Episode of 2019.

Yesterday we added unit tests for a component that uses the Intl API to a frontend project. Everything worked flawlessly on our local machines, but it failed on CI. The failing tests showed a number formatted in English instead of the expected German format.

A good architect maximises the number of decisions not made

— Robert C. Martin in Clean Architecture

Most web services I worked with use a MVC-style architecture, with a handlers package and, if at all, a repository package. While this may be great for small services, the handlers package introduces a big problem: It mixes transport logic with business logic. This makes refactoring hard (imagine switching your HTTP framework) and therefore forces you to make decisions about these kind of things before even starting the project. So when I started a new project recently, I decided to use the hexagonal architecture (aka Ports and Adapters) and so far I’m really happy.

If you’re using Vim, you know that feel (if you aren’t, you can skip this

article): Everytime you open a project, you toggle

NERDTREE and

Tagbar (or similar). But you don’t

want to put that in your .vimrc, because then they’d open every time, even

when you just want to quickly edit a file.

You’re deploying your Octopress blog via Git to GitHub Pages (or Heroku), but you don’t like Heroku and GitHub Pages are refreshing too slow and you really don’t want to use Rsync, do you?

Just deploy to your own server via Git.